Former Lithuanian President Valdas Adamkus: Since that moment when you take the oath, your private life is eliminated forever

The archives of Gabija Žukauskaitė’s family

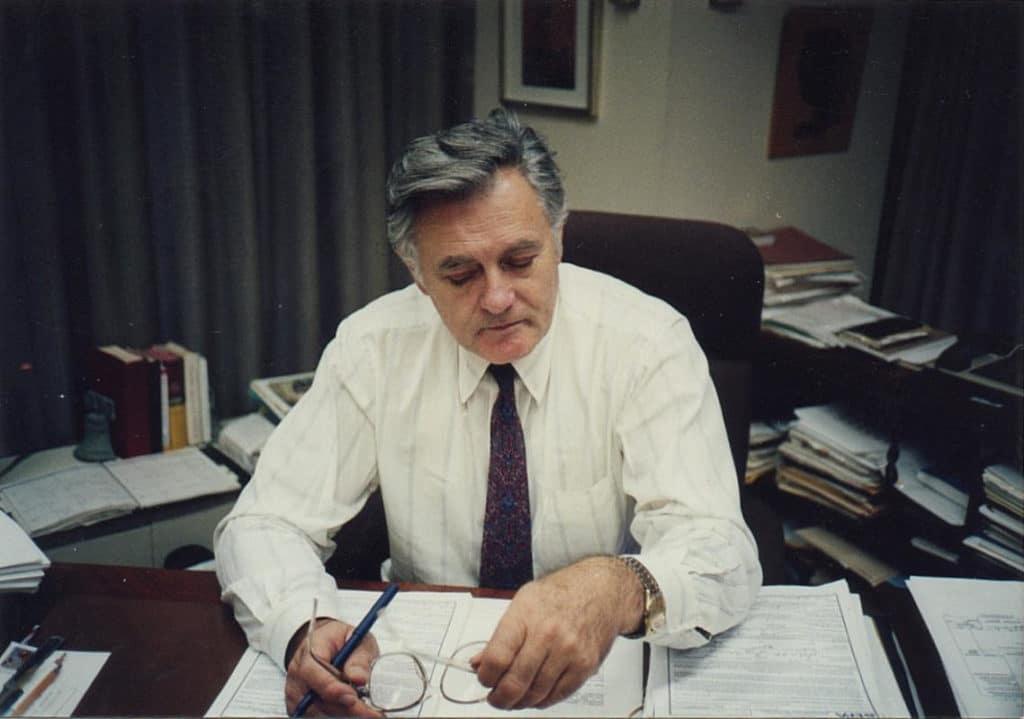

To Americans, Valdas Adamkus is known for cleaning up pollution in Lake Michigan and the other Great Lakes; to Lithuanians, as a president who brought new western standards to the country, thus changing the face of Lithuania in perpetuity.

It would be possible to write an entire volume of Lithuanian history according to Valdas Adamkus’ biography. He grew up in Kaunas, an interwar capital of Lithuania. Growing up, his best friends included the son of the third Lithuanian president, Kazys Grinius, and the brother of Vytautas Landsbergis, the first Lithuanian leader after Soviet control. During the Nazi occupation, they began publishing an underground, anti-German newspaper titled, ‘Youth, be on duty!’ Adamkus fought alongside insurrectionists against Soviet rule, though later he was forced to leave the homeland. Nevertheless, he persistently continued his activities abroad. In 1948, Adamkus contributed significantly while competing at the Olympic Games of the Enslaved Nations. Winning two gold and two silver medals in track and field events, Adamkus is now regarded as the fastest president in the world, with a time of 10.8 seconds in the 100-metre dash. In the summer of 1949, Adamkus went to the United States with his family, and settled into a Lithuanian-American community in Chicago. His life journey, in many ways, mirrors that of the hopeful American Dream – Adamkus started off with just five dollars in his pocket before finding work in a car parts factory. Eventually, he earned a degree from the Illinois Institute of Technology and began working at the newly established US Environmental Protection Agency. Finally, after fifty years of Soviet occupation, Adamkus returned to his motherland and became the president of the Republic of Lithuania in 1998, serving for two terms (1998-2003 and 2004-2009). Even at the age of 92, Valdas Adamkus still continues to rank as one of the most influential political figures in Lithuania.

Karolina Savickytė.

Karolina Savickytė.Chronologically, January, February and March include some of the most significant events for Lithuania – Freedom Defenders’ Day, Restoration of the State Day, Restoration of Independence Day. Mr. President, what do each of those dates mean to you, especially because you have been perceived as the person who has connected two epochas of independent Lithuania?

Both the February 16 and the March 11 in a moral and spiritual sense are very similar. February 16 marks the day when the Council of Lithuania unanimously adopted the Act of Independence in 1918, declaring Lithuania an independent state. The March 11 was the day that Lithuania declared itself independent from the Soviet Union in 1990. There is only one difference; the February 16 inspired and united people, who, despite very difficult circumstances, still cherished love and focused on creating their own state. Comparatively, the March 16 commemorates the restoration of Lithuania after the long fight against occupation which lead to its coronation with receiving independence. It showed that our nation, in the first phase of its independence (from 1918 till 1940, Ed.), was able to rear the strongly patriotic younger generation, who took the strength from their parents and built the state of Lithuania on a firm, moral legs. It held that there was a strong aspiration for independence during those 50 years of occupation, and it proved to the world that we are determined to live freely and autonomously. These celebrations keep us vital and break the routine, where we are faced with various concerns about people’s well-being and the problems of our system in general. The reminiscences of celebrations is something that strengthens us and induces us not to refuse such ideals. After a long time we – however, translated in a more realistic sense – are realizing and will continue to realize, as we move this path forward.

I am a granddaughter of a deportee myself and I grew up listening to my granny’s stories from her time in Siberia (during the period 1941-1953, approximately 130,000 Lithuanians were exiled to remote areas of the USSR, in Siberia, the Arctic Circle areas or Central Asia, Ed.). She always emphasized the symbolic importance of the February 16. Granny liked to tell how that day was remarked by her family – although they were thousands of kilometers from the homeland, they were at least together in thoughts with Lithuania. And how were you – personally and collectively with other Lithuanians – commemorating this date in the so-called free world?

In emigration we did not have such a problem because our whole generation of emigrants was not one of economics but purely political. The withdrawal from Lithuania was against occupation directed protest, which had an aim to get back our freedom and independence. The February 16 became, to us, the source of spiritual strength, which maintained Lithuanianness, determination, and efficiently fighting whilst seeking Lithuanian independence. I think that the ceremonies of commemorations themselves did not differ from the commemorations of the interwar Lithuania period. Everything was solemn. And not only in the ranks of one’s people’s, but also highlighting it in the foreign communities that we were living in.

Karolina Savickytė

Karolina SavickytėIn one of your books I saw the picture of Marquette Park, where a crowd of Lithuanians with our countries’ attributes is depicted. The whole action was held alongside the square, nearby the home of the Chicago mayor. Was this also a particular tradition?

Yes, traditionally it was held in the very center of Chicago. Others often wondered how we managed to get the favour of the city government – because we almost stopped the traffic with our Lithuanian gatherings! Lithuanian flags, solemn speeches… Folk dance groups even used to make short performances! I would say that the celebration of Lithuanian independence was mentioned in astonishing circumstances, turning it to the attention of Americans as well.

In the United States, the main center of Lithuanian culture is undoubtedly the city of Chicago. The first Lithuanian emigration wave settled down in Bridgeport, but afterwards moved to Marquette Park, and finally to Lemont. How did Americans evaluate that kind of Lithuanian suburbs? What about other foreigners? How did Lithuanians integrate into other state’s life?

To my mind, the question of integration is not related to the founding of Lithuanian suburbs in one or another place that you have mentioned. It was self-contained, uniting itself with a goal to keep the nationality and further develop Lithuanian culture. In my opinion, the concentration of Lithuanians in those separate suburbs led to more permanence – Americans also payed attention to this. They – various officers attending our concerts or celebrations, for instance – were surprised by our national group, which, despite being far away from the motherland, was not only able to save the identity, but also mature it over the years. It kept hope that matters in the issues of Lithuanian freedom will get better someday. I’m personally proud of our emigration, which managed to achieve such significant results – Lithuania’s case for independence became famous worldwide.

I was amazed by your, Mr. Raimundas Mieželis’ and other active Lithuanians 1956 initiative of petition to the president Dwight D. Eisenhower. You sought that the USA, either by using its direct influence on the Soviet Union or through organizations like the Red Cross, start caring about the destiny of Lithuanian deportees. How did you manage to collect the signatures of Lithuanians while having so little time? Bearing in mind, these times were no Internet or other improvements of communication.

Well, firstly, I succeeded in making a very effective, main organizational committee from all organizations which involved Lithuanian youth. It was an unprecedented incident – to bring together all our active youth organisations’ managements, people who were united by one common purpose. It showed that organizations which existed in the United States had a sufficiently sturdy foundation to deal with tasks like the latter. The leaders of the organization, who formed the core of our committee, spread out the petition within their organizations, signing pages all throughout America. Later, we just simply needed to gather and bind them and present it to the president. So, we knew we had a certain target, we knew we had a limited time and we got our job done.

Karolina Savickytė

Karolina SavickytėIn a fact, at that time president Dwight D. Eisenhower had some serious health problems and he was replaced by vice president Richard Nixon. How did the meeting go? Was it your first visit to the Capitol, the White House?

As far as it concerns me and youth organizations, yes, it was the very first time. Because before that, privilege, or I can even say the monopoly, was in the hands of Lithuanian American Council (LAC), which was the main American organization guiding the political life of emigrated Lithuanians. But this time it was a different, new, and I believe, for some people unexpected deed, demonstrating that Lithuanian youth can also do something individually and achieve it. Indeed, your observation was correct: it was truly the first time, when in a form of organizational youth, we appeared in the highest state layers.

And what was the impression when you – young people – got so much attention?

Of course, I can answer only for myself. I was happy knowing that our idea finally turned into reality. We received a big resonance not only in our press but also in a wide, American press. Our deed rang through the American Congress because the delegation was accredited there, as well as

in Senate. To conclude, it was not simply a one or two hour performance to American society. It actually echoed from one corner of the country to another.

Which of the American politicians in those days were the most disposed towards Lithuanians? Maybe understood Lithuanian wounds the best?

Many… I don’t think I’m able to name all of them.

But maybe there is somebody whom you’d like to thank?

The fact that American press, television, and radio made that issue known for the American people was an achievement already – and that Americans accepted it with benevolence. As much as we could, we also expressed our gratitude to local American politicians and governors through the Lithuanian organizations in various American states.

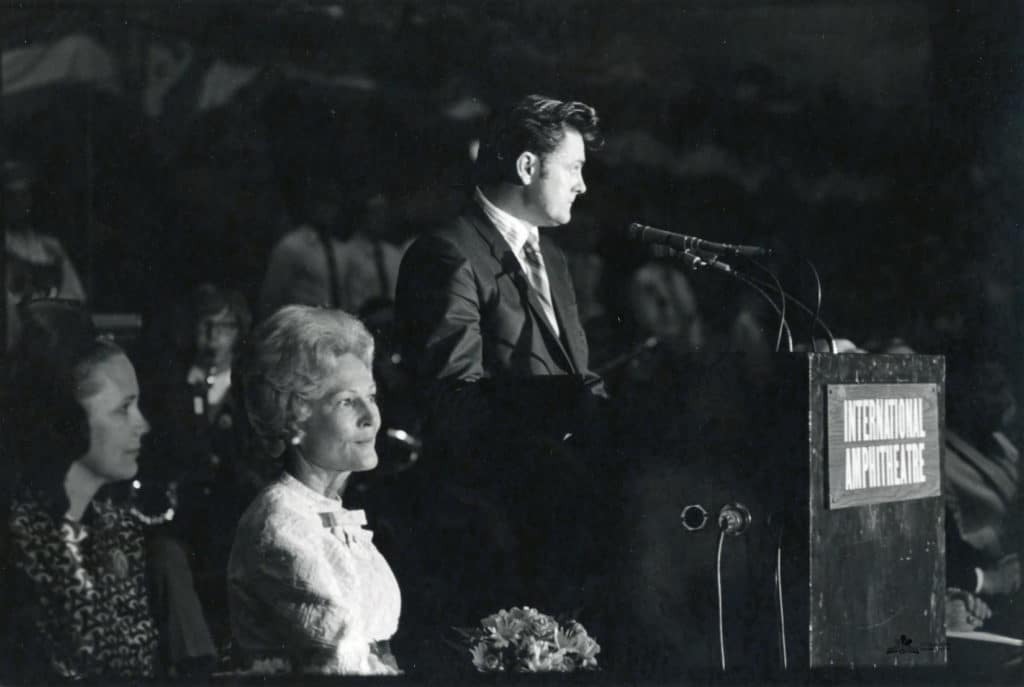

It’s also worth mentioning that you invited U.S. first ladies – in 1972 Patricia Nixon, in 1976 Betty Ford – to the Lithuanian Folk Dance Festival. How did you manage to do that?

It may be a bit uncomfortable to say but under existing, favourable conditions, using my official status in a relatively high American governmental service, I was able to gain access to the right people – members of government, Congressmen. I simply used those chances by exploiting my personal connections. What concerns the appearances of the first ladies, of course, it gained a huge amount of attention. We astounded all national groups in the United States. Throughout the entire country rang the announcement of Mrs. Nixon’s arrival to an opening ceremony of the Folk Dance Festival. Many people later were calling me with the question, ‘How?’ It was the first time when a person of such a rank participated in an event of national group. It was a big surprise for all but for us it was more of the recognition.

Lithuanian Research and Studies Center archives

Lithuanian Research and Studies Center archivesHow did the lives of Lithuanian emigrants change after the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953? What was the reaction of the American officers and media?

As far as my memory lets me remember, the news about Stalin’s death spread around the globe. I’m not sure if I could somehow exclusively comment on that matter from the perspective of Americans but for Lithuanians… I believe that some of us in the deepest corner of heart had a sensation of relief. One of the biggest offenders of the Lithuanian nation passed away. We perceived new possibilities for raising the question of Lithuania’s independence. As later history has shown, this hypothesis was quite right because figures like Mikhail Gorbachev came out and many things in the system started changing. New movements appeared in the Soviet Union itself, which also touched our lives as well. In conclusion, albeit we didn’t think that the sky was falling, it encouraged us that there might be more opportunities to achieve our goal in the future.

Karolina Savickytė

Karolina SavickytėYou spent a big part of your life with „Santaros-Šviesos“ (Concord-Light, Ed.) federation and its activities – the periodicals, books, conferences and congresses. Without any doubt it had an enormous impact on the Lithuanian political thought and the high culture formation. You also personally knew many bright-minded Lithuanian emigrants. Who among them, in your opinion, are undeservedly forgotten nowadays? What would you recommend for future generations to investigate in a field of emigrated Lithuanians’ intellectual heritage?

It’s a complicated question to answer. I don’t know if I could all that easily pick out who is forgotten. Perhaps I see the lack of general analysis of Lithuanian emigrants’ contribution covering their creative strengths or emphasizing their works. On the other hand, I think at least the main creators for the Lithuanian audience are known. I’d like more of them to be included in our educational system, so that’s why I guess it more concerns of the teaching aspect. It’s important that our young generation be interested in it while studying and learning. Nevertheless, our emigration, even in such difficult conditions, managed to keep the spirit of creativity alive and supplement the common Lithuanian cultural heritage.

When I visited library of your name (President Valdas Adamkus Library, Ed.) in Kaunas I saw with my own eyes how many new shipments were brought in – many boxes of books from USA, including the personal collection of Aleksandras Štromas. I thought then there is still so much undiscovered about Lithuanian emigrants’ heritage. Because I finished high school relatively recently, I can comment that the topic of lives of emigrants is rarely spoken in schools. It is mostly disclosed during the Lithuanian language and literature lessons, when pupils inspect novels by Marius Katiliškis or Antanas Škėma. Meanwhile history lessons are quite silent on this subject.

I agree with you totally. And, as I have noticed, there should be more attention payed at analyses of emigration’s ability to save cultural identity. For instance, examination of results – what it gave to the common Lithuanian culture and the domain of Lithuanianness’ preservation.

In some previous interviews you have mentioned that the values of your promoted liberalism differ from the current Lithuanian liberalism. Could you please tell us what those essential distinctions include?

It’s hard to point a finger at it and name it. In my opinion, general striving or, in other words, I don’t see the proclamation’s that ‘we organize, conduct and move by liberal way’ realization in Lithuania. Maybe it is caused by outside imperfections which emerge from social conditions. Liberalism had no appropriate foundations to form in Lithuania. In that field we feel that we lack guides and leaders, and that our liberal idea drowns. Sometimes it seems to me that the liberal thought itself – the promotion of free word, free will and free mindset – is distorted in Lithuania. Thinking that liberalism opens any liberties which deny the main moral values, deform the liberal ideal and converting it, in some cases, creates chaos. The only hope that over time a certain group of people will remain, they won’t turn away from set liberal ideals, and then liberalism itself will become valid as one of the essential idealogical domains. But, I’ll repeat myself, this will take a matter of time.

I also hope that eventually Lithuanian society will get mature enough and we’ll have all indications needed for the full-grown democratic country.

On the other hand, it would be naive to expect that we’d be capable of implanting that ideal, whereas the Western world has been pushing its for way several centuries.

Since its formation, the United States has had a two-party system. Which political party was more common among Lithuanian emigrants? Why did you decide to become a Republican?

The bigger part of ‘the new’ (1940’s, Ed.) emigration were Republicans. Why? In the years of the Democratic-controlled US government the Yalta conference and other conferences were held. We felt, and I also felt, that we were sold to the Russian communism. During emigration we were always involved with political discussions. It was very hard to work our way through the international society. At that time, Republicans felt, let’s say, a different rear and were closer to us. They clearly and fearlessly declared their position against the communist order. That’s why the new emigration went, without saying, for the Republicans. Meanwhile ‘the old’ emigration (1905’s, Ed.) was consisted mostly of working class people who were from the agricultural sphere. And democrats always proclaimed to be those who represented and defended rights of that group exploited by capitalists. There was a collision between ‘the new’ and ‘the old’ emigration. Of course, I cannot one hundred percent affirm that the new emigration was only Republican and the old one was only Democratic, but the tendency was noticeable.

For 27 years you have worked in the United States Environmental Protection Agency. You were an administrator of the Fifth Region (Mid-West) and when you retired from the EPA in 1997, you had the longest tenure of any senior executive. Which skills that you gained came in handy while serving as the President of Lithuania?

Generally speaking, those 27 years in a high administrative office allowed me to cooperate with different countries as the representative of the United States. I have met many politicians and members of government. The experience of holding an office gave me much deeper understanding about the international problems. So, I could say that I came to the presidential post not from the street but with experience of almost a quarter of a century.

You became acquainted with different U.S. presidents. Are there any characteristics which would unify all of them?

I couldn’t say anything concrete. But I can mention that from the six U.S. presidents with whom I worked directly, I could mark out president Ronald Reagan. I was impressed by his sincerity, warmth and humanness. Reagan was especially disposed towards our Lithuanian ideas. He firmly spoke on the question of Lithuanians receiving national rights, and he more than once approved this attitude internationally – first during the fall of Berlin Wall and then in the context of further events.

What kind of things should Lithuanian politicians learn from the U.S. leaders?

The political culture in general. Though we had to endure a period when there weren’t any chances to grow in surroundings of Western views, we still had to suffer the shortage of it. Well, I hope that while living with today’s conditions, we’ll learn those lessons. I believe in the young generation of

our politicians. They have all possibilities to follow what is going on in the world and how other various, contemporary political leaders are reacting – there are plenty of great examples in the Western world. And from all of those experiences, we’ll develop a certain political level ourselves.

Karolina Savickytė

Karolina SavickytėHow does it feel to put your hand on the Constitution and utter aloud the words of the presidential oath?

It’s hard to describe in words. During this minute you feel such tension that you don’t even realize the importance of that instant. Just later when you start the service you take the responsibility and perceive how deep, meaningful and binding this oath is. The only thing which I’d like to say, especially, for the young generation, is that when you swear to the Constitution, you have to respect it, fight for the free man and his natural rights, and it will completely eliminate your private life. Since the moment you take that duty, you refuse your personal goals. Your aim from now on is to give your state and its people everything that you have with the best of your personality and your environment.